Paul Thek

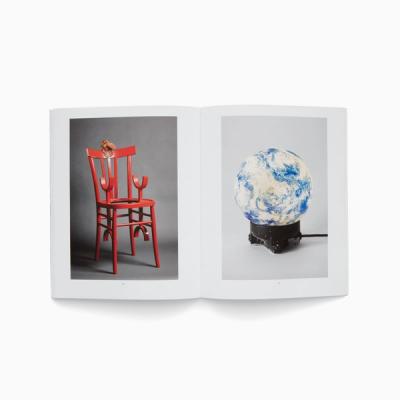

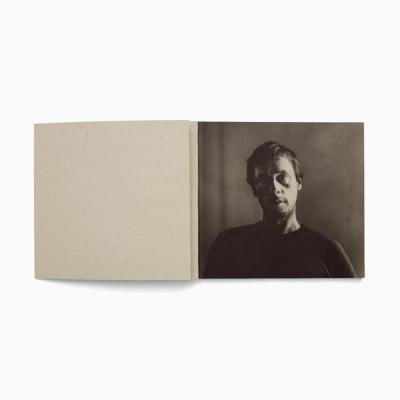

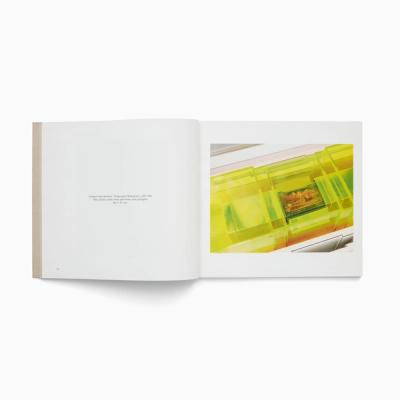

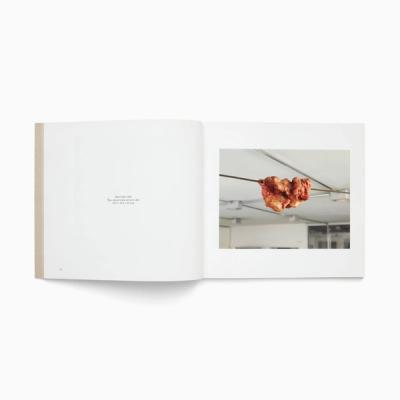

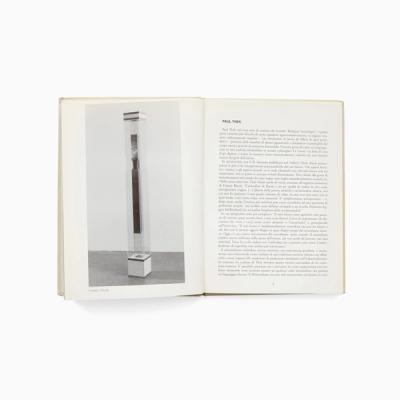

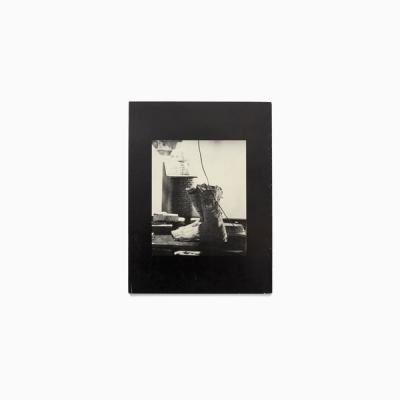

Paul Thek's artistic career began in the early 50s, pursuing studies in New York City at the Art Students League, the Pratt Institute, and Cooper Union School of Art, eventually leading him to Miami, where he found an artistic community that included set designer Peter Harvey, photographer peter Hujar, and playwright Tennessee Williams. A decade later, he burst onto the New York scene with a groundbreaking solo exhibition at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery, showcasing his “meat pieces,” later referred to as his Technological Reliquaries series, consisting of hyper-realistic wax sculptures depicting hunks of flesh—both human and otherwise. Inspired by a visit to the Capuchin catacombs in Palermo in 1963, Thek's Technological Reliquaries catapulted him to the forefront of the art world, challenging Pop and Minimalism with an idiosyncratic approach that merged earnest posthuman embodiment and a critique of contemporary art trends. His renown continued to grow with the early support of Pace Gallery, marked by his inclusion in a 1965 group exhibition alongside Richard Artschwager, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Morris, and Lucas Samaras, followed by a solo presentation in 1966, introducing new works from the Technological Reliquaries series encased in colored Plexiglas vitrines.

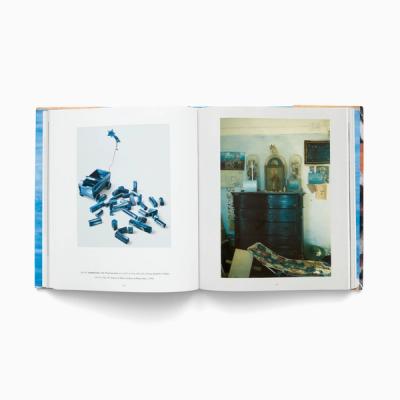

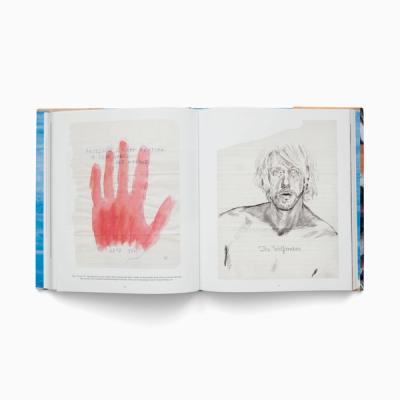

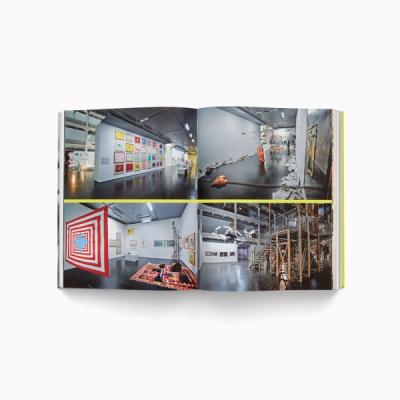

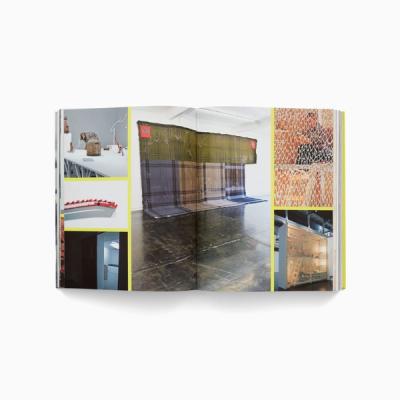

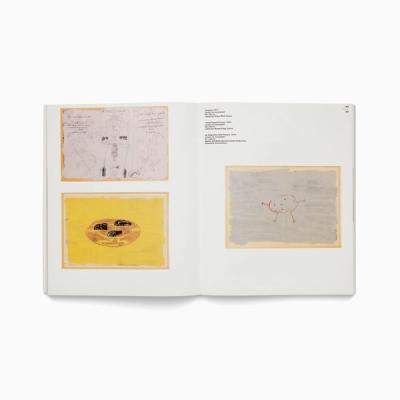

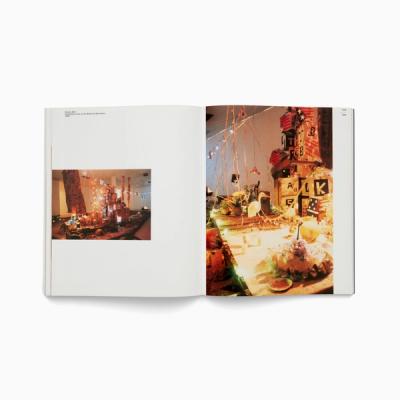

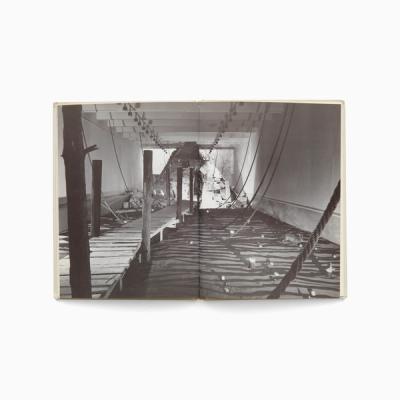

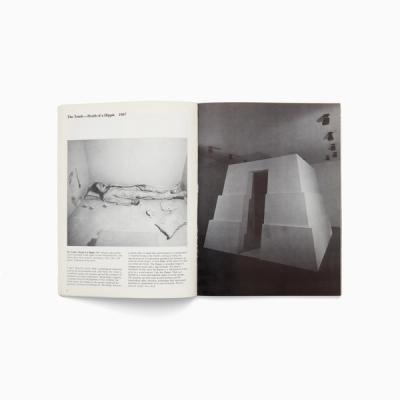

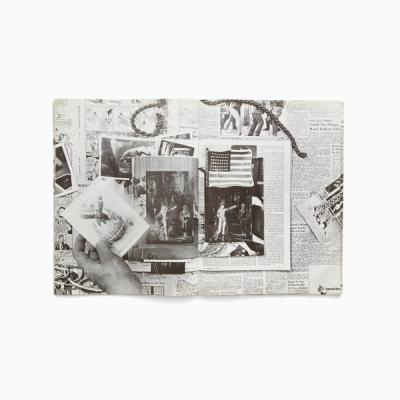

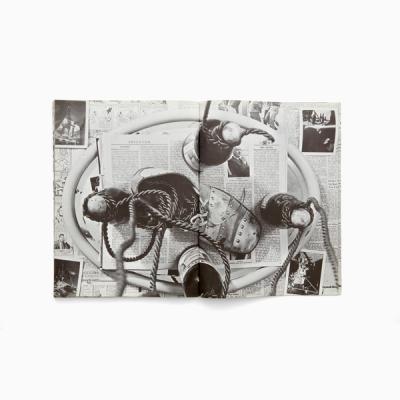

In 1967, Thek unveiled The Tomb or "Dead Hippie," a wax figure cast from his own body presented inside a small wooden ziggurat, which he constructed inside the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Largely interpreted as a critique of the Vietnam War, the piece stirred controversy and mainstream attention. Following this, Thek spent most of the next decade in Europe, where he pioneered a new mode of exhibition-making that involved the creation of elaborate, ephemeral installations composed of sand, candles, newspaper, chicken-wire, Polaroids, and discarded furniture, assembled into ad-hoc environments by a group of collaborators called “The Artist’s Co-op.” Returning to New York in the 80s, Thek worked extensively creating paintings on newspaper, which constitute a major portion of his later artistic production, since his installations of the 70s and 80s were largely ephemeral and exist today only as residues, artifacts, and fragments. The form of the newspaper and its link to the march of day-by-day reality underscores the poignant examination of temporality in Thek’s practice. “My work is about time,” he wrote in one of his notebooks, “an inevitable impurity from which we all suffer.”

Visual Bibliography

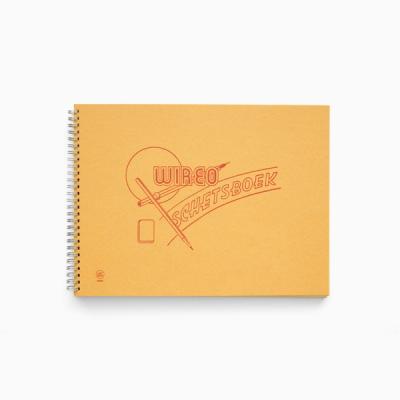

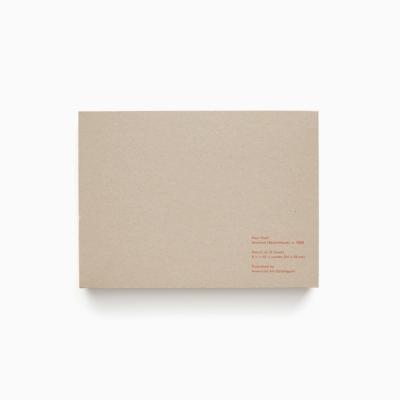

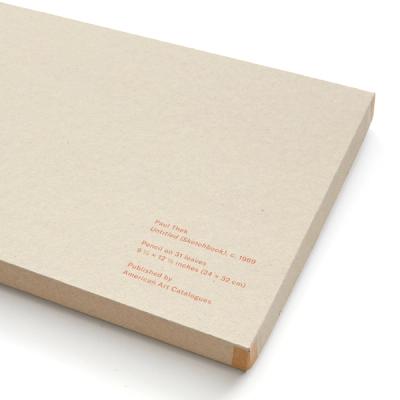

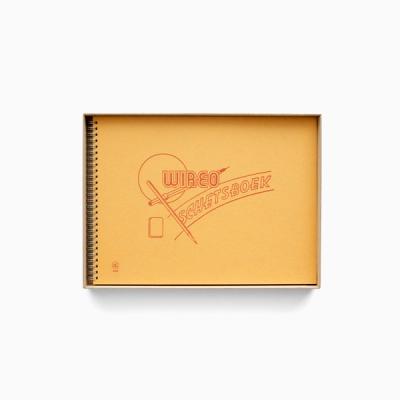

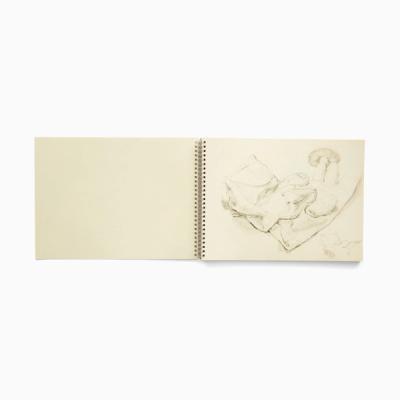

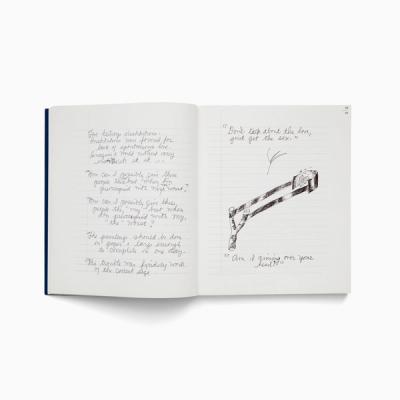

Paul Thek: Untitled SketchbookPaul Thek2024publications

Paul Thek: Untitled SketchbookPaul Thek2024publications From Cross to CribPaul Thek2015archive

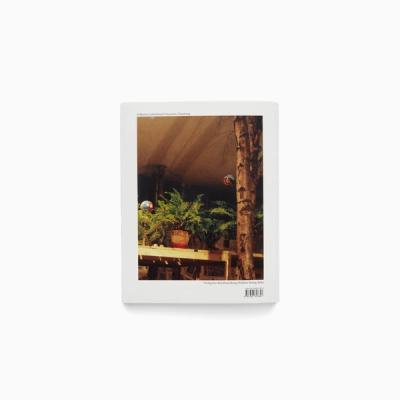

From Cross to CribPaul Thek2015archive Paul Thek - Nothing but Time: Paul Thek Revisited 1964-1987Paul Thek2013archive

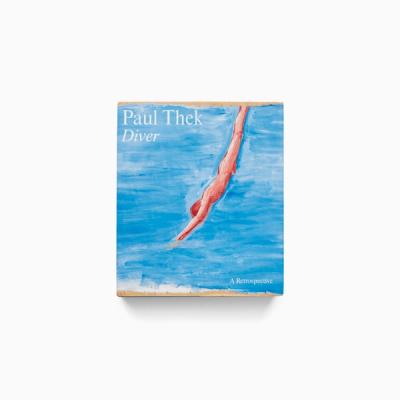

Paul Thek - Nothing but Time: Paul Thek Revisited 1964-1987Paul Thek2013archive Diver, A RetrospectivePaul Thek2010archive

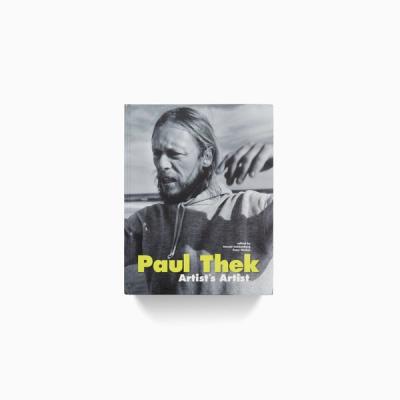

Diver, A RetrospectivePaul Thek2010archive Paul Thek: Artist's ArtistPaul Thek2009archive

Paul Thek: Artist's ArtistPaul Thek2009archive Paul Thek Paintings, Works on Paper, and Notebooks 1970–1988Paul Thek1998archive

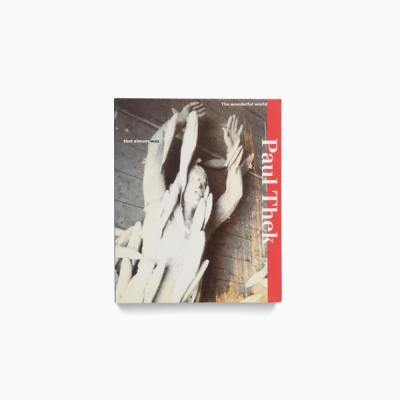

Paul Thek Paintings, Works on Paper, and Notebooks 1970–1988Paul Thek1998archive The Wonderful World That Almost WasPaul Thek1996archive

The Wonderful World That Almost WasPaul Thek1996archive Paul ThekPaul Thek1992archive

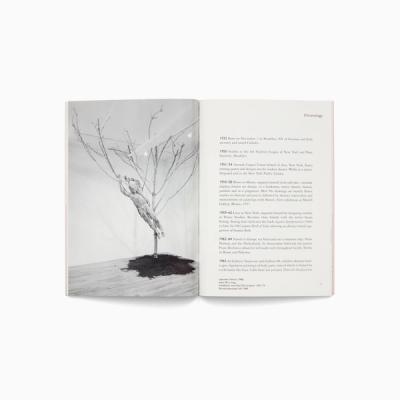

Paul ThekPaul Thek1992archive ProcessionsPaul Thek1977archive

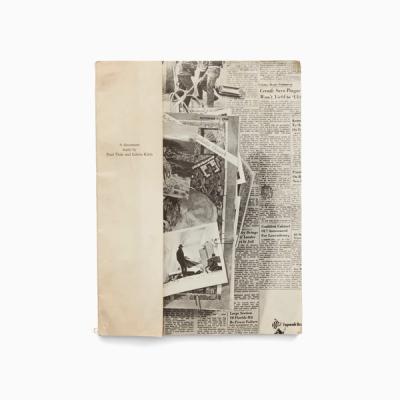

ProcessionsPaul Thek1977archive A Document Made by Paul Thek and Edwin KleinPaul Thek1969archive

A Document Made by Paul Thek and Edwin KleinPaul Thek1969archive